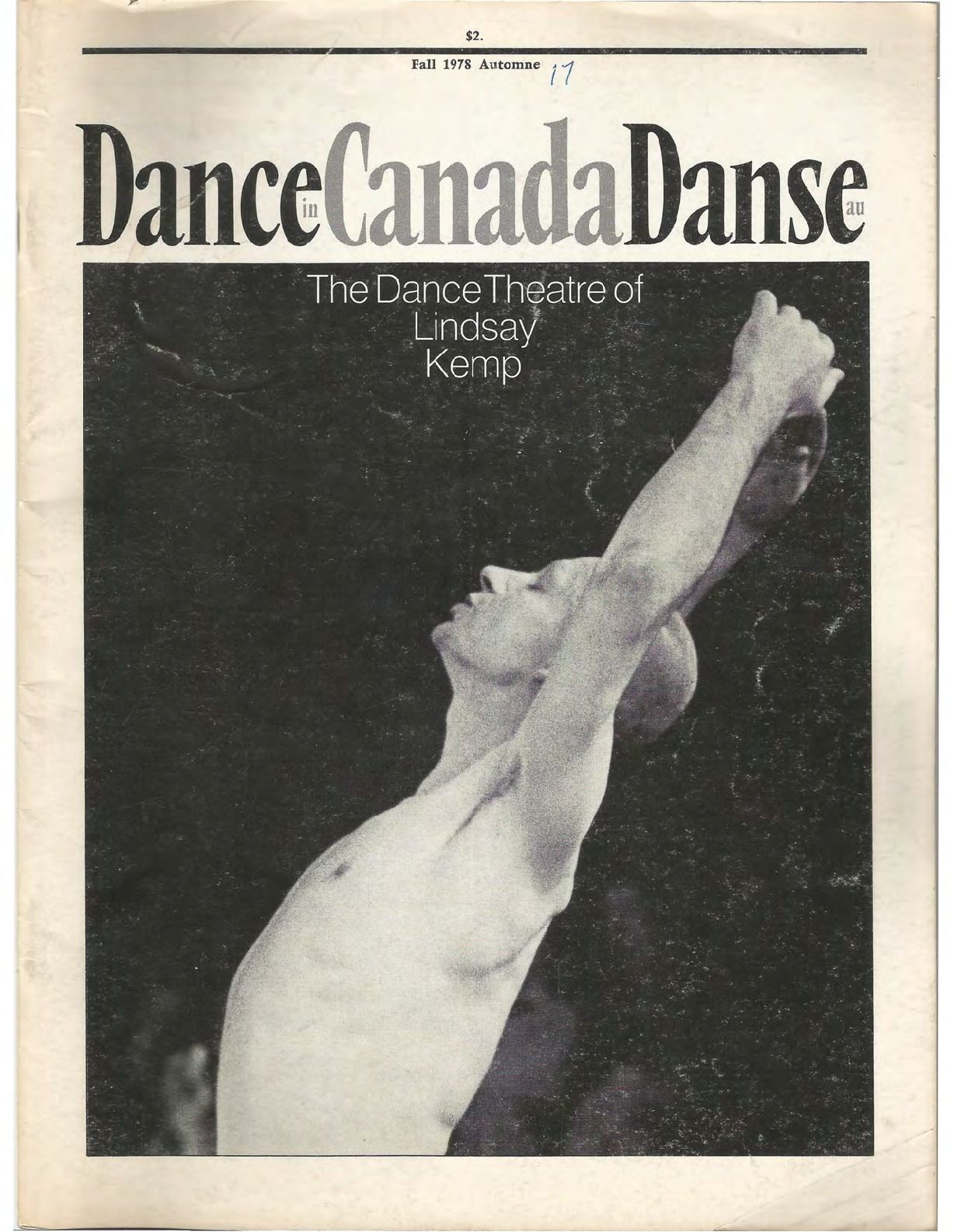

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 17, Fall 1978

Added 30th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 8th Mar 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- The Dance Theatre of Lindsay Kemp by Graham Jackson

- The Month of the Long Days: The First Canadian Choreographic Seminar: A Diary by Elizabeth Zimmer

- Choreography: A Modest Proposal by Jock Abra

- Training the Dancer V: Turnout by Rhonda Ryman

- In Review

-Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Choreography

Vancouver

Jock Abra

Modern Dance

Michael Crabb

Andrew Oxenham

Elizabeth Zimmer

Penelope Doob

Selma Landen Odom

Lawrence Adams

Miriam Adams

Romeo and Juliet

Alicia Alonso

National Ballet of Cuba

Lauretta Thistle

Men and Dance

Andra Smith

Graham Jackson

John Butler

Mary Fraker

Oscar Araiz

Jean A. Chalmers Award in Choreography

Robert Desrosiers

Rhonda Ryman

Marijan Bayer

Karen Jamieson

Karen Rimmer

Echoes

American Ballet Theatre

Holly Small

Martha Graham

Kinesiology

Kati Vita

Leland Windreich

Carlos Miranda

Linda Rabin

David Vaughan

Reciprocal Innervation

Louis Robitaille

Clifford E. Lee Choreography Award

Ian Gibson

Lindsay Kemp

Flowers

Robert Cohan

Adam Gatehouse

Jennifer Mascall

Frederick Ashton

Joseph H. Mazo

Beryl Grey

David Gillard

Charles Payne

Anton Dolin

Lyn Roewade

Lise Bernier

Kathryn Brownell

Gary Wahl

Shinju

San Francisco Ballet

Jorge Esquivel

Angele Dagenais

Ballet Nacional de Cuba

Ricardo Abreut

Ace Buddies

Christopher Bannerman

Mimi Beck

Chantal Belhumeur

Lucia Chase

City Ballet of Toronto

Lew Christensen

La Compagnie de Danse Jo Lechay

Dansepartout

Malcolm Forsyth

Le Groupe Nouvelle Aire

Marine Heppner

The House

Doris Humphrey

Judith Miller

Meredith Monk

Tomm Ruud

Michael Smuin

Eddy Toussaint

Metamorphosis

Watch Me Dance You Bastards

Preludes

Betrothal

Concerto

Pavane

Gems

Renderings

Maxine Heppner

Absinthe

Cradling

Round Dance

Plateau

Raw Recital

Tablet

Women of the Tent

Trilogy

Robyn Simpson

I Remember What's-His-Face

Songs of Mahler

Cantate

Reflexions

Choreographers

National Choreographic Conference

Benesh Notation

Turnout Technique

Description of the objects in this Item

01/10/1978

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 17, Fall 1978

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item