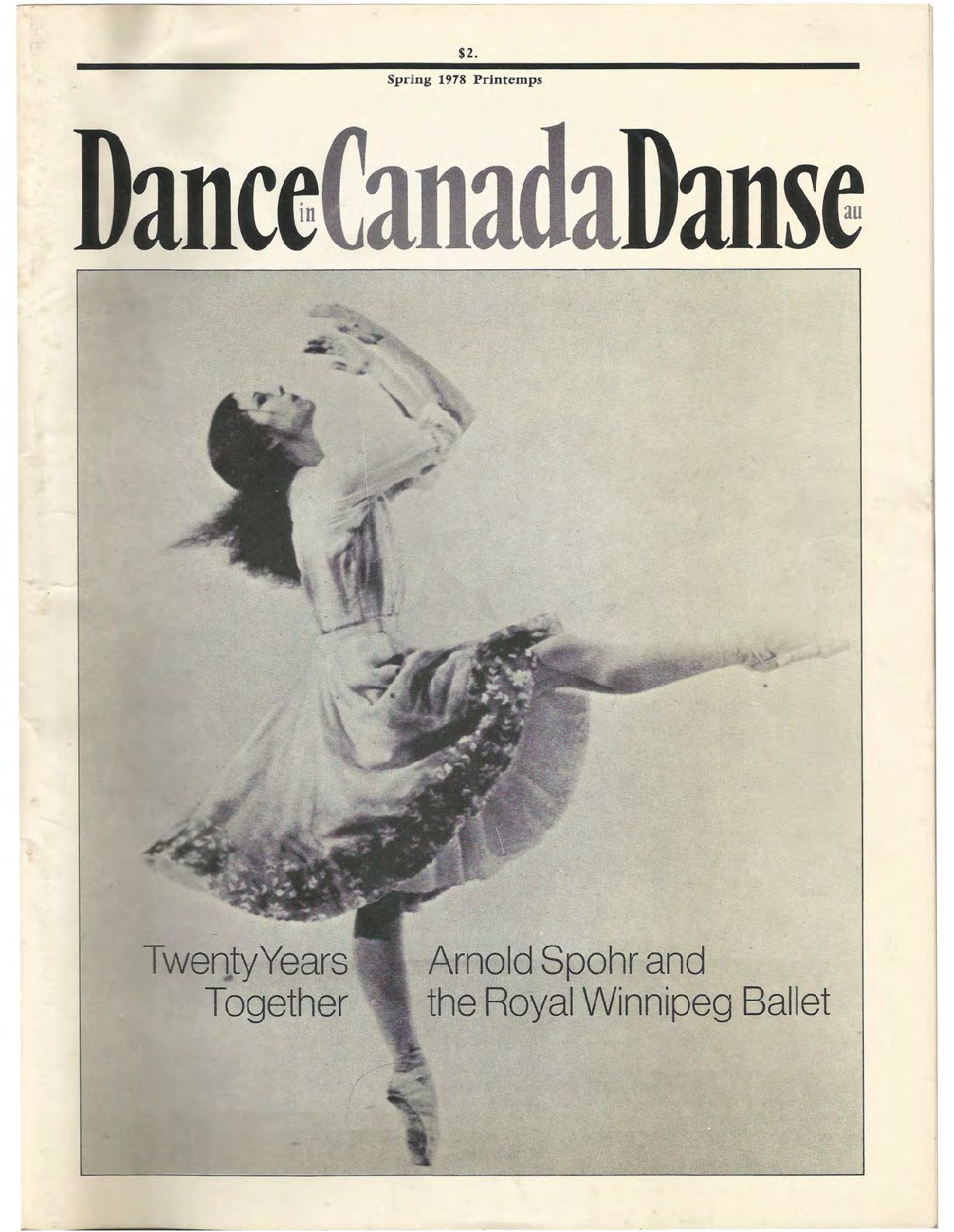

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 15, Spring 1978

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 2nd Mar 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

-Editorial by Michael Crabb

- 'I could have been lying in the sun' Arnold Spohr at the RWB

- Troubled Decades: Les Grands Ballets Canadiens at 20 by Lauretta Thistle

- Greener Pastures: Le Groupe de la Place Royale in Ottawa by Charles Pope

- Training the Dance III: New Approaches and a Challenge to Tradition by Rhonda Ryman

- In Review

- Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Royal Winnipeg Ballet

Ballet

Alicia Markova

Dance in Canada Association

David Earle

Peter Randazzo

Le Groupe de la Place Royale

Toronto Dance Theatre

Modern Dance

Training

Fernand Nault

Ludmilla Chiriaeff

Michael Crabb

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens

Awards

Ballet Ys

Film

Karen Kain

Arnold Spohr

Christopher Darling

Jean-Pierre Perreault

Peter Boneham

Sir Frederick Ashton

Regina Modern Dance Works

The Royal Ballet

Lauretta Thistle

Mary Jago

Sallie Lyons

Susan Macpherson

Casimir Carter

Elizabeth Chitty

Lora Burke

Mary Fraker

Rhonda Ryman

Eileen Thalenberg

J. Groo Bannerman

Karen Rimmer

Mikhail Baryshnikov

Jeffrey Ballet Company

Kyra Lober

Tay

Astral Light

Nanti Malam

Repertoire

Charles Pope

Mary Johnston

Robert J. Pierce

Marcia B. Siegel

Kevin Singen

Kati Vita

Leland Windreich

F. Matthias Alexander

Irene Apiné

Anne Bancroft

Leslie Browne

Mary Clarke

Dance Plus Four

Maya Deren

Linder Doeser

Anthony Dowell

Peter Dudar

Lily Eng

Allegra Fuller Snyder

Murray Geddes

Danny Williams Grossman

Albert Laberge

Shirley MacLaine

Margaret Mead

Gaby Miceli

Carlos Miranda

Keith Money

Claudia Moore

Linda Rabin

Sara Rudner

Sara Rudner Performance Ensemble

Anna Sokolow

John Travolta

Trisha Brown and Company

David Vaughan

The Dream

Love Songs

Les Nouveaux Espaces

Extreme Skin

True Bond Stories

A Concert

Steve Dymond

Grandpa's Spells

Tapestry

Mythos

Couples

Curious Schools of Theatrical Dancing: Part I

Ecce Homo

Higher

National Spirit

Tryptych

Charlotte Hildebrand

Dance for a Gallery

Real Suite

The Trilogy Suite

Missing Associates

Carmina Burana

La Scouine

Tommy

Borders, Boundaries and Thresholds

Recital

Goose

Ballet Premier

Children of Men

Line Up

Balinese

Baroque Dance 1675

Ideokinesis

Independence

Mythology

Reciprocal Innervation

Religion and Dance

Rolfing

Saturday Night Fever

Structural Integration

Tap Dance

Television

Sandra Naiman

Marie Marchowsky

Rina Singha

The Turning Point

Valentino

Louis Robitaille

Kathryn Greenaway

Description of the objects in this Item

01/04/1978

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 15, Spring 1978

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item