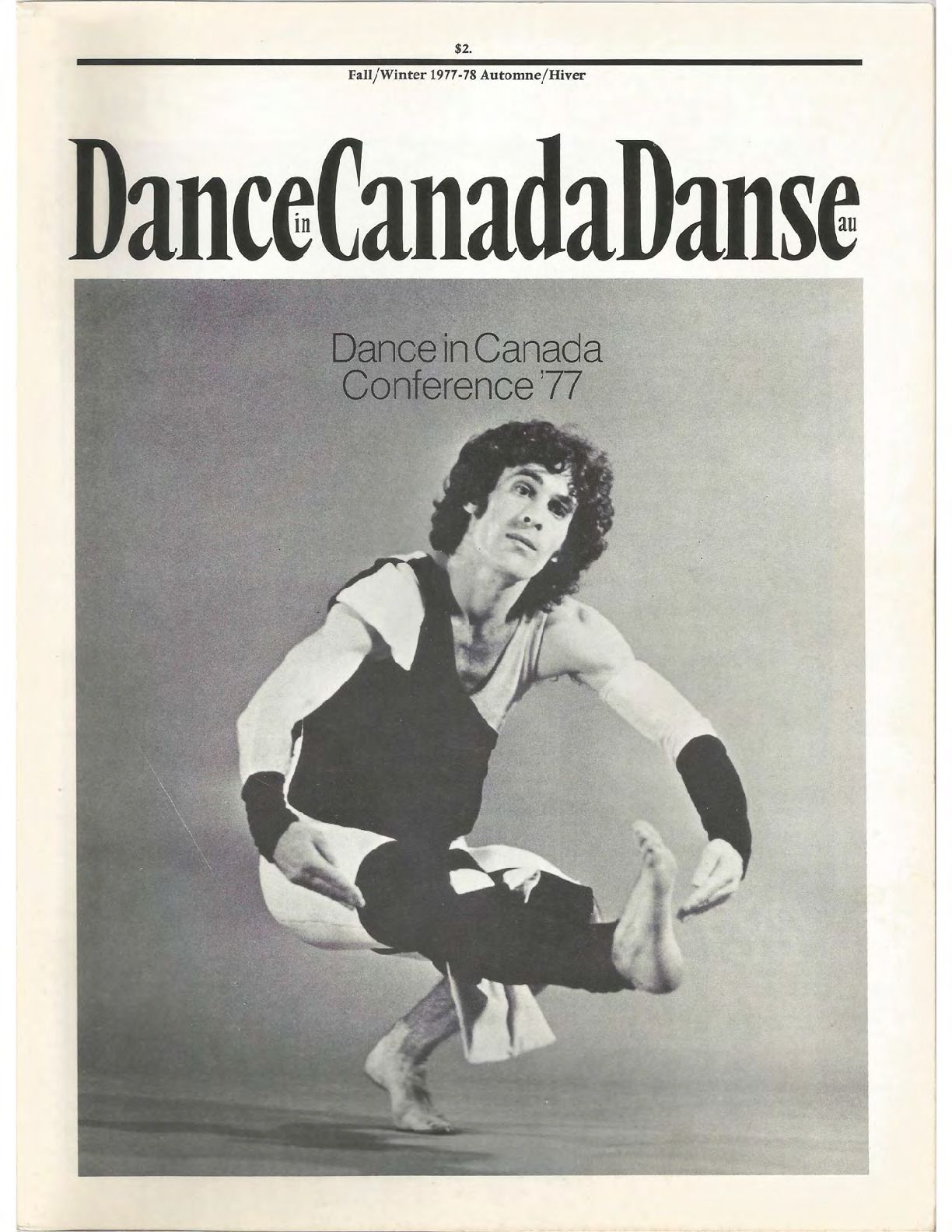

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 14, Fall/Winter 1977/1978

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 2nd Mar 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- Editorial by Susan Cohen

- Dance in Canada Conference '77: Many Minutes of the Meeting by Elizabeth Zimmer

- Growing Pains by Michael Crabb

- Three Philosophical Approaches to Dance by Rose Hill

- Northern Saskatchewan Diary by Maria Formolo

- Profile: Peter Randazzo by Virginia Solomon

- Training the Dancer II by Rhonda Ryman

- Letters from the Field

- In Review

- Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Choreography

Royal Winnipeg Ballet

Pedagogy

Touring

David Earle

Peter Randazzo

Susan Cohen

Le Groupe de la Place Royale

Toronto Dance Theatre

Michael Crabb

Conferences

Betty Oliphant

Maria Formolo

Veronica Tennant

Monique Michaud

Grants

Elizabeth Zimmer

Style

Lawrence Adams

Twyla Tharp

Jean-Pierre Perreault

Virginia Solomon

Regina Modern Dance Works

Nighthawks

Lauretta Thistle

Graham Jackson

Mary Fraker

Oscar Araiz

Adagietto

Continuum

Peter and the Wolf

Audiences

Rhonda Ryman

Workshops

Rose Hill

American Ballet Theatre

Holly Small

Artpark

Mikhail Baryshnikov

David Best

Agnes Mille

Beryl Dunn

Eliot Field

Iris Garland

Martha Graham

Jeffrey Ballet Company

Robert Jeffrey

Lincoln Kerstein

Tamara Karsayma

Kyra Lober

Martha Graham Dance Company

Fred Mathews

Lubomyr Melnyk

Kelly Rude

Marine Sheets

Tay

Unicorn, the Gorgon and the Manticore

The Nutcracker

Agnes de Mille

Astral Light

Luna

Mbira

Nanti Malam

Amber Garden

L'Assassin Menace

I Had Two Sons

The Letter

A Simple Melody

Starscape

Visions for a Theatre of the Mind

Jupiter's Moon

Andrea Smith

Keith Urban

David Weller

Housing

Aesthetics

Directors

Contact

Juries

Kinesiology

Dance in Literature

Manuels Technique

Phenomenology

Repertoire

Jackie Malden

Robert Greenwood

Books on Dance

Rite of Spring

Joan Sinclair

Toronto Free Theatre

Groupe Nouvell'Aire

Description of the objects in this Item

01/10/1977

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 14, Fall/Winter 1977/1978

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item