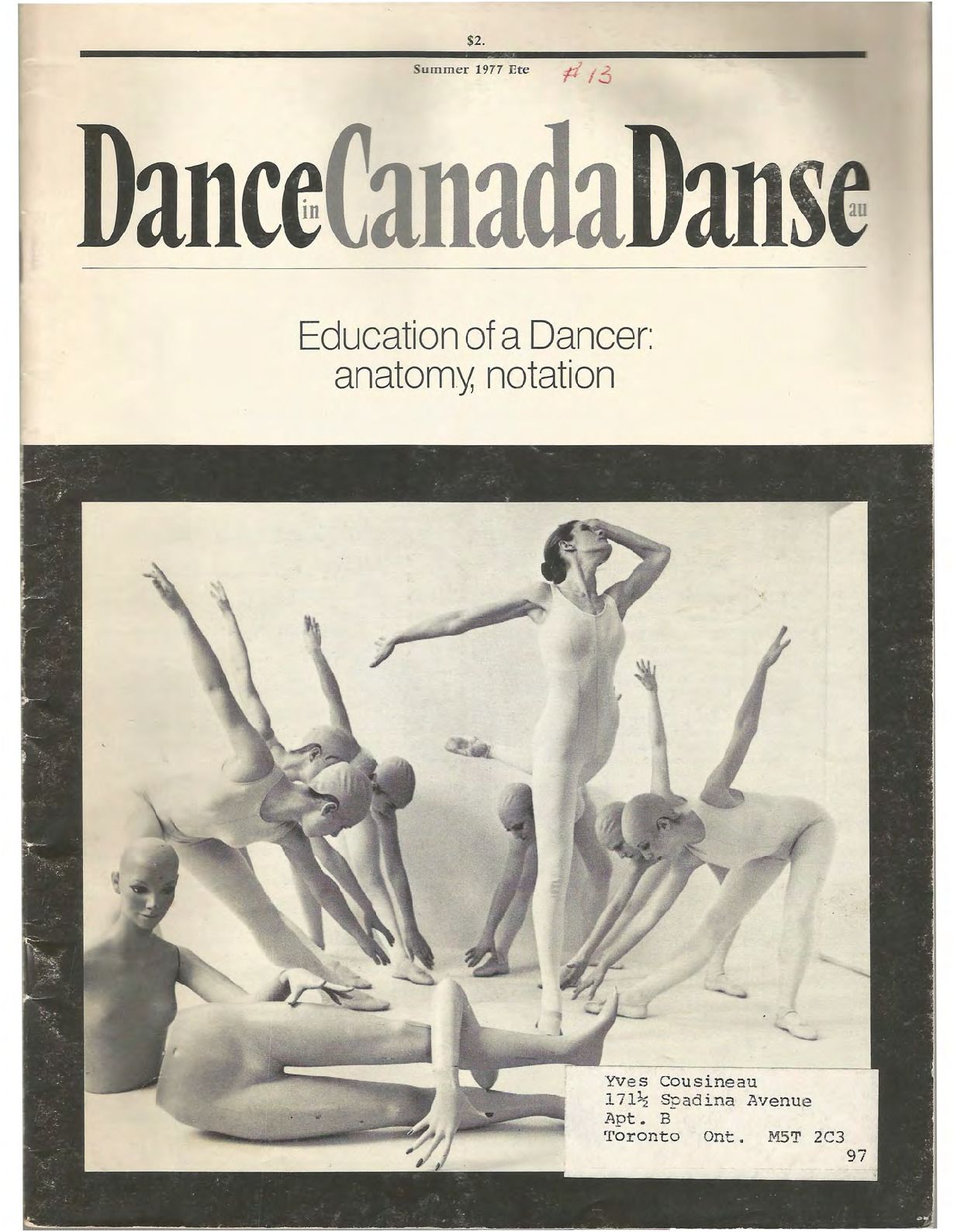

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 13, Summer 1977

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Kelly (Collections Manager and Archivist, DCD) / Last update 1st Mar 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- Editorial by Susan Cohen

- The Terminal City Connection by Elizabeth Zimmer

- Training the Dancer I: The Roots of Today by Rhonda Ryman

- The Bournonville Schools by Sondra Lomax

- Profile: Mikhail Berkut by Eileen Thalenberg

- Graham Training Settles in Canada by Graham Jackson

- Letters from the Field

- In Review

- Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Toronto

Vancouver

Ballet

Terminal City Dance

David Earle

Susan Cohen

Anna Wyman Dance Theatre

Toronto Dance Theatre

Schools

Training

Michael Crabb

Erik Bruhn

Patricia Beatty

Marijan Bayer Dance Company

Anna Blewchamp

Anna Wyman

Elizabeth Zimmer

Judith Marcuse

Entre-Six

Dance History

Grant Strate

Style

Auguste Vestris

Paula Ross

Paula Ross Dancers

La Sylphide

Lise Brunel

Graham Jackson

Lawrence Gradus

Rhonda Ryman

Sondra Lomax

Mikhail Berkut

Eileen Thalenberg

J. Groo Bannerman

Tournesol

Savannah Walling

Doug Gallant

R. Bruce Metcalfe

Anne-Marie Gaston

Marijan Bayer

Vincent Dienne

John Gruen

Donald Himes

Terry Hunter

Karen Jamieson

Karen Rimmer

Ted Kivitt

Cynthia Lyle

Patricia BcBride

Ivan Nagy

Jean-Georges Noverre

Kirsten Ralov

Marie Taglioni

Kei Takei

School of the Toronto Dance Theatre

Martine van Hamel

Violette Verdy

Echoes

Momentum

Apassionata

Poem of Man

Konservatoriet

En Mouvement

Toccata

Babar

Old Man Coyote and Creation

Generation

Apart

A Diary

Trips

Klangenfort

Deflections

Quicksilver

Sixes and Sevens

Tremolo

Two People

Costume

Culture Shock

Eurythmics

Benesch Notation

Labonotation

Stretching

Strength

Technique

Graham Technique

Bournonville Technique

Tubular Bells

Workshops

Eighteenth Century Dance

Sandra Caverly

Paris

Description of the objects in this Item

01/07/1977

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 13, Summer 1977

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item