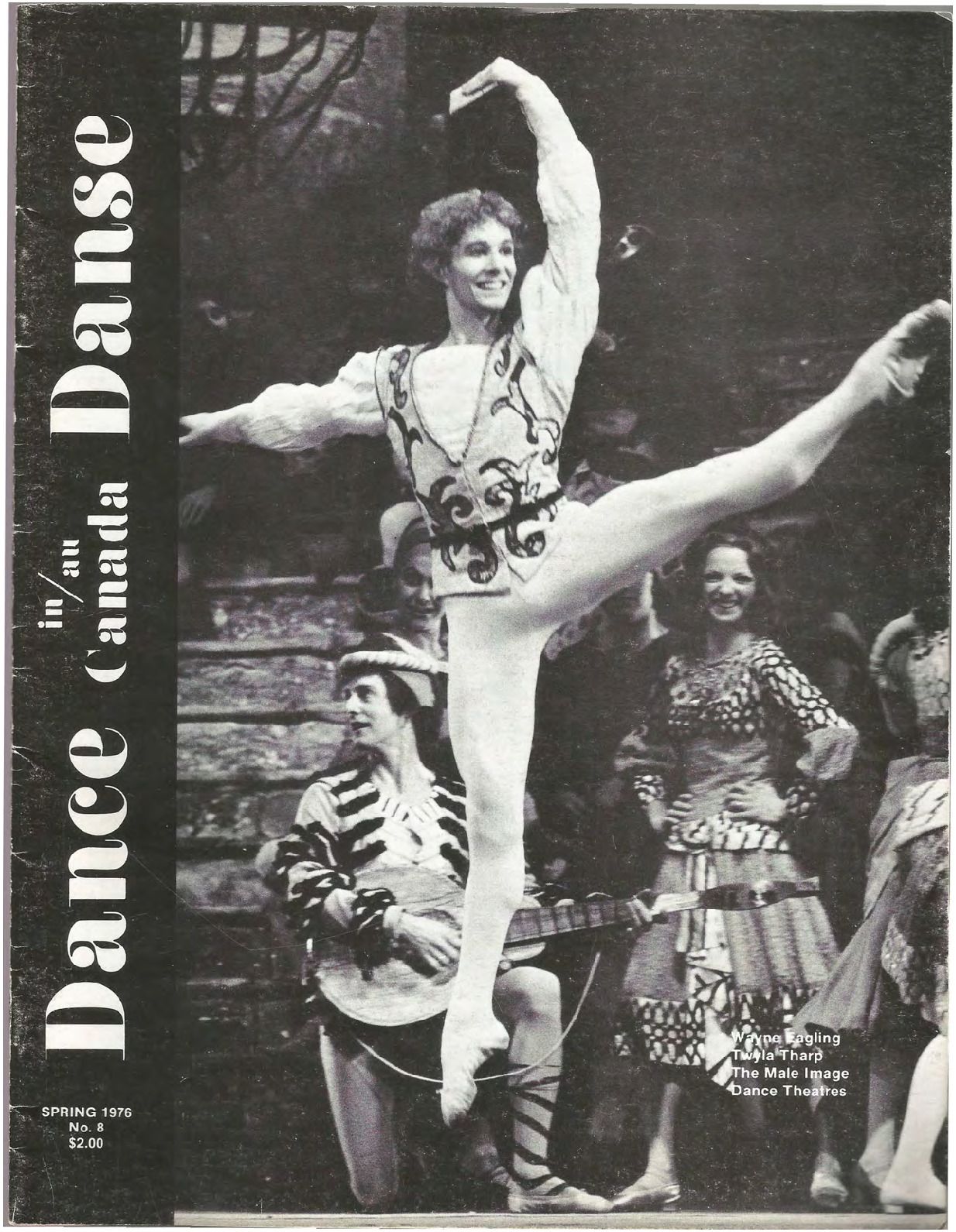

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 8, Spring 1976

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 20th Feb 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- Editorial by Susan Cohen

- Brass Foundry to Dance Lab by Susan Swan

- The Little Church Around the Corner by Elizabeth Zimmer

- Wayne Eagling: A Dancer Prepares by Penelope B.R. Doob

- Profile: Twyla Tharp by Nancy Goldner

- Meditations on the Male Image by Penelope B.R. Doob

- Review by William Littler

- Noticeboard

- Letters from the Field

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Choreography

Toronto

Vancouver

British Columbia

Ontario

Ballet

Susan Cohen

Modern Dance

Education

Schools

Brian Macdonald

Fernand Nault

Ludmilla Chiriaeff

William Littler

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens

National Ballet of Canada

Erik Bruhn

Veronica Tennant

Agents

Ann Ditchburn

Elizabeth Zimmer

Penelope Doob

Dance History

Teachers

Auguste Vestris

Brydon Paige

Christopher Wooten

Constantin Patsalas

Fernando Bujones

Frank Augustyn

Frank Bourman

Gary Norman

Igor Youskevitch

James Kudelka

Kenneth MacMillan

Lawrence Adams

Lesley Collier

Merce Cunningham

Miriam Adams

Nancy Goldner

Paul Taylor

Paula Ross

Pierre Mercure

Rudi van Dantzig

Rudolf Nureyev

Seda Zaré

Susan Swan

Terry McGlade

Tomas Schramek

Twyla Tharp

Vaslav Nijinsky

Wayne Eagling

15 Dance Laboratorium

Ballet Trockadero de Monte Carlo

Paula Ross Dancers

Paylychenko Dance Company

Royal Ballet

Vancouver East Cultural Centre

Visus Foundation

Artere

Cantate pour une Joie

Colonel Sanders

Coppelia

Day in the Life of a Brick

Deuce Coupe

Eight Jelly Rolls

La Sylphide

Kisses

Liberté tempérée

Monument for a Dead Body

Monument for a Dead Boy

Push Comes to Shove

Romeo and Juliet

Sue's Leg

Swan Lake

Symphony in 75

The Bix Pieces

The Fugue

The Sleeping Beauty

Composers

Interpretation

Men in Dance

The Brinson Report

Description of the objects in this Item

01/04/1976

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 8, Spring 1976

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item