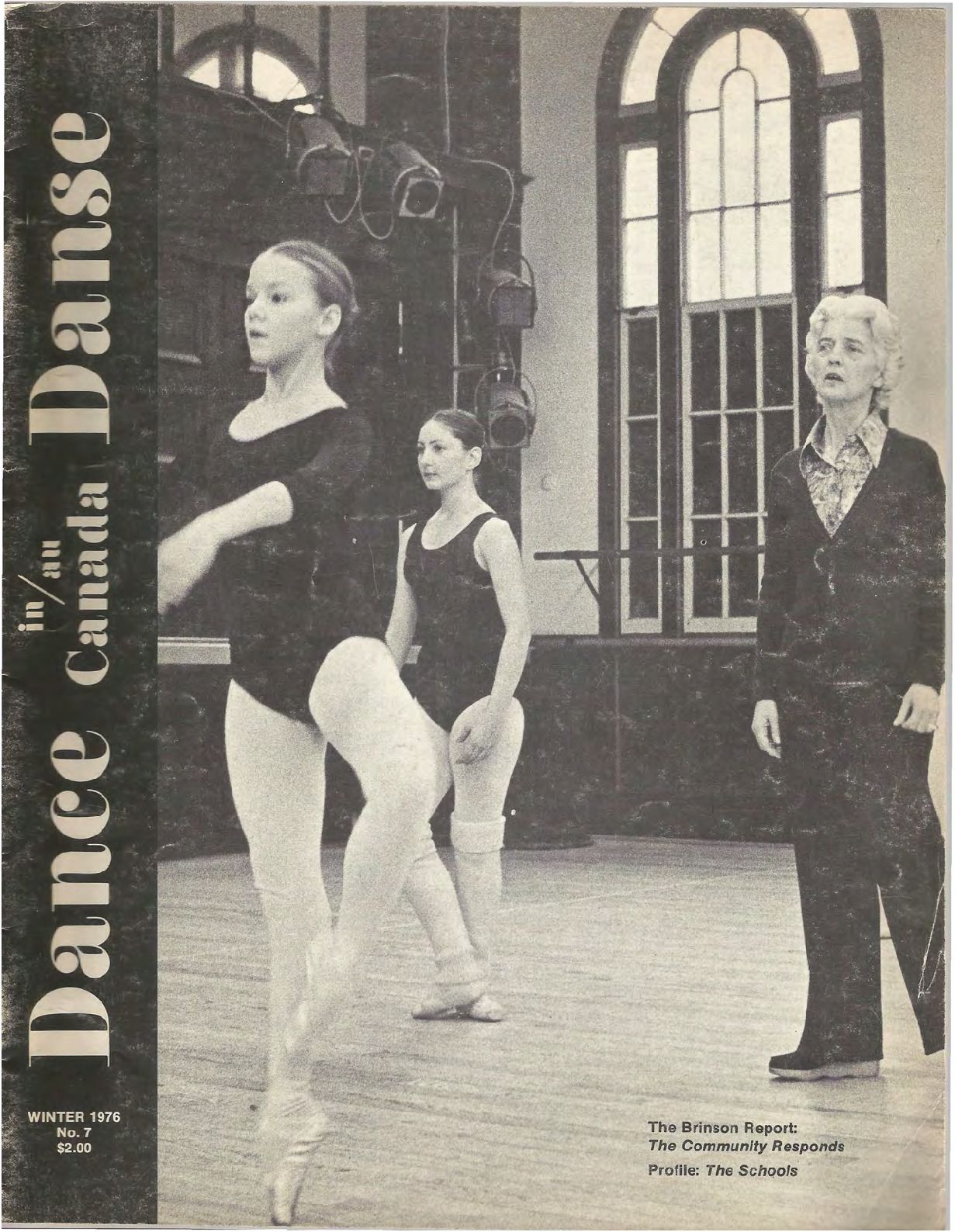

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 7, Winter 1976

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 20th Feb 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- Editorial by Susan Cohen

- Profile: The Schools by Michael Crabb

- The Brinson Report by Peter Brinson

- The Future? Other Views by Grant Strate, Betty Oliphant, Ludmilla Chiriaeff, Fernand Nault, David Moroni, Arnold Spohr

- Dance 1984 by Brian Macdonald

- Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Royal Academy of Dance

Ballet

Susan Cohen

Education

Schools

Training

Brian Macdonald

Celia Franca

Fernand Nault

Ludmilla Chiriaeff

Michael Crabb

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens

National Ballet of Canada

Betty Oliphant

Peter Brinson

National Ballet School

Grants

Entre-Six

Dance History

Arnold Spohr

Christopher Darling

David Moroni

Galina Panov

Grant Strate

Valery Panov

Banff Centre School of Fine Arts

Island Dance Ensemble

L'Ecole Superieure de Danse

Imperial Society of Teachers Dancing

The Royal Winnipeg ballet

Classical Ballet

Hands

Satire

Style

Teachers

The Brinson Report

Description of the objects in this Item

01/01/1976

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 7, Winter 1976

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item