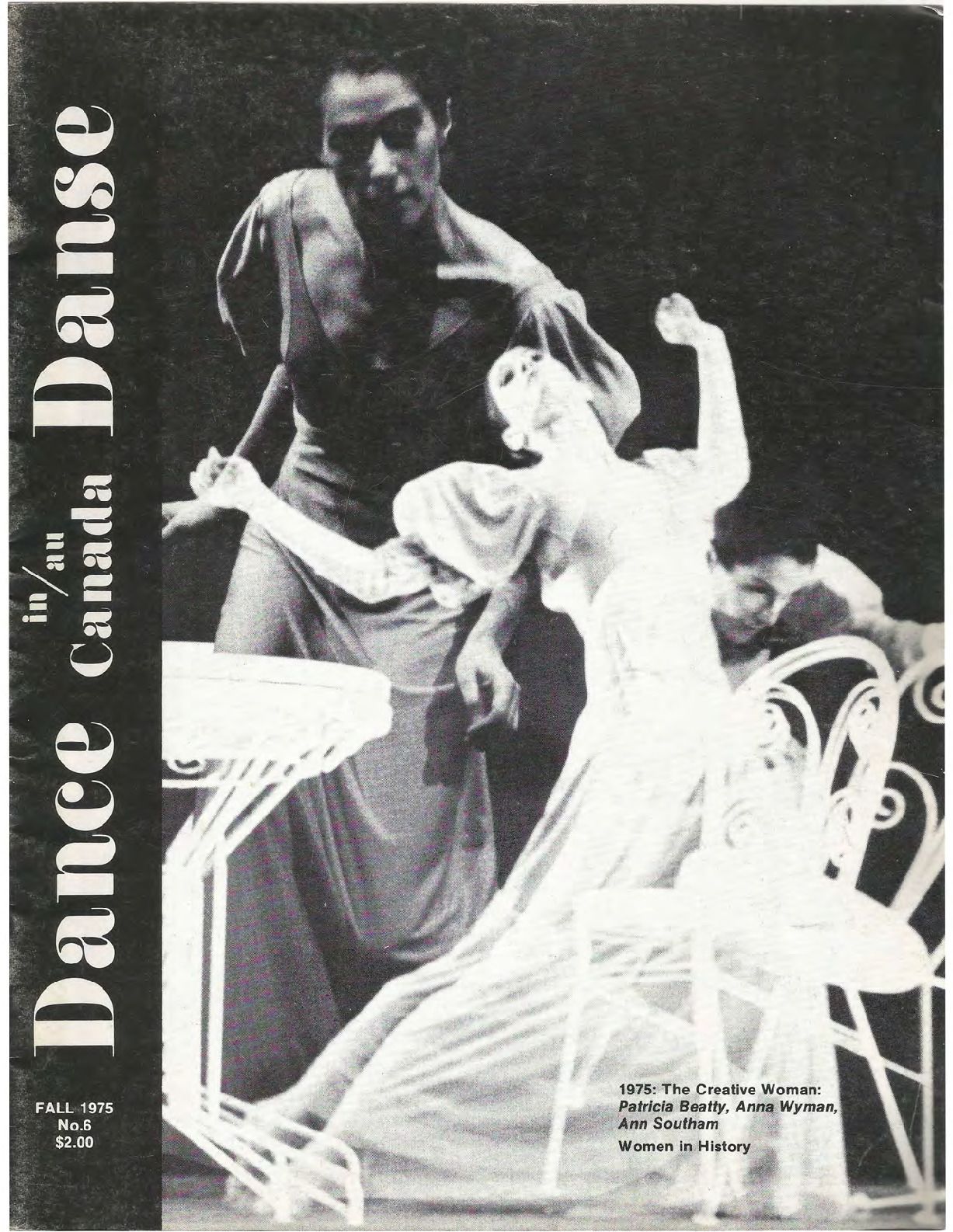

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 6, Fall 1975

Added 29th Apr 2021 by Beth Dobson (Archives and Programming Assistant, DCD) / Last update 18th Feb 2022

The description of this Item

Contains the following articles:

- Editorial by Susan Cohen

- We Are Magicians by Anna Blewcamp

- In Search of Women in Dance History by Selma Landen Odom

- Profile: Ann Southam by Ulle Colgrass

- Anna Wyman: Not for the Uncommitted by Elizabeth Zimmer

- Review by Penelope Doob

- Noticeboard

The collections that this item appears in.

Tag descriptions added by humans

Choreography

British Columbia

Ballet

Collaboration

Susan Cohen

Anna Wyman Dance Theatre

Toronto Dance Theatre

Modern Dance

Brian Macdonald

Celia Franca

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens

Patricia Beatty

Ballet Ys

Ann Ditchburn

Ann Southam

Anna Blewchamp

Anna Wyman

Elaine Bowman

Elizabeth Zimmer

Henriette Hendel

Jehan Tabourot

Jennifer Muller

Judith Marcuse

Margo Sappington

Marie Saile

Mile de la Fontaine

Penelope Doob

Sam Dolin

Selma Landen Odom

Ulle Colgrass

Ursula Hanes

Virginia Woolf

Entre-Six

The Royal Winnipeg Ballet

Against Sleep

An American Beauty Rose

baby

Dance is... This... And This

Encounter

Here at the Eye of the Hurricane

Juice

Klee Wyck: A Ballet for Emily

Number One

Reprieve

Rodeo

Strangers

Study for a Song in the Distance

Undercurrents

Composing

Dance History

Feminism

Music

Sexism

Women

Description of the objects in this Item

01/10/1975

Magazine

Dance in Canada Magazine Number 6, Fall 1975

Dance Collection Danse

DCD's accession number for this Item. It is the unique identifier.

Auto-generated content

Tag descriptions added automatically

Auto-generated identification of objects in this Item

An autogenerated description of this Item

Auto-generated number of faces in the Item